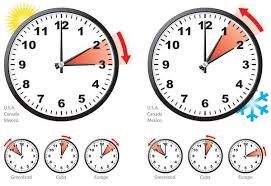

Smartodds loves Statistics would like to remind you that the clocks go back an hour this weekend.

You probably heard that the EU is planning to end the practice of switching between ‘summer’ and ‘winter’ times, in which clocks are artificially moved back and forward by an hour at the end of October and March respectively. The rationale for this procedure of so-called daylight saving is closely linked to historical social, agricultural and industrial demands on energy supplies, but what was relevant a century ago, when the practice was first devised, is rather less relevant today.

Some media stories also suggest that putting an end to daylight saving is rather more urgent. For example: “Daylight Savings Time Literally Kills People“. Or even more dramatically: “Why Daylight Saving Time will Kill us All“.

In part there is some basis to these stories. Messing slightly with people’s regular sleep patterns can induce extra tiredness, and there is some evidence that over an entire population this can lead to an increase in the number of driving-related and other accidental deaths. The effect is very slight though, and really says more about the effect of sleep-deprivation on accidental deaths than it does about daylight saving per se.

Rather more surprising and intriguing though is an apparent increase in the rate of heart attacks on the day after clocks go forward an hour in March, with a similar decrease on the day after they go back in October. A recent study published by the British Medical Journal found that there was a 24% increase in patients presenting for acute heart attacks on the day after clocks go forward, and a 21% decrease on the day after clocks go back. This was based on a study of many patients over several years, and so the differences are too big just to have occurred by chance. So what’s going on? Does daylight saving give people heart attacks?

Well, the first thing a statistician will do is look for other factors which might explain the results. For example:

- Since clocks always change early on a Sunday morning, are Sunday, or maybe Monday, generally different from other days of the week in terms of heart attack rates, regardless of the clock change effect?

- Are there more heart attacks generally at some times of the year compared to others?

The answer to both these questions is yes, but in the analysis reported by the BMJ both of these effects, and others, were accounted for, so the unusual increases and decreases following daylight saving time changes are after such allowances have been made. So again, what’s going on? Does moving the clocks induce heart attacks?

Well, not really. When the researchers of the BMJ study counted the number of patients attending hospital with heart attacks within the entire week following a change in daylight saving, rather than just the next day, then they found no difference at all following the time change in March or October. Perhaps for physiological or social reasons, heart attacks appear to be slightly delayed – on average – after the change in October, and sped up after the change in March. So if you look only at the days immediately following the change, it does look like the change itself is changing the rate of heart attacks. But over a slightly longer window of a week or so, there’s no evidence of a change at all.

In summary, moving the clocks forward or backwards won’t induce anyone to have a heart attack who wasn’t going to have one anyway; the change might just cause someone’s heart attack to occur slightly earlier or later in the same week.

There seem to be two useful messages from this:

- As with Simpson’s paradox, we see the danger of simply carrying out a statistical analysis without taking into account the context. Testing the daily data for whether is a change in heart attack rates when clocks are changed suggests there is an effect. But understanding the context of the problem and looking at the data over a slightly longer timespan indicates that there is no real change.

- The media are often just interested in a good story, and won’t let concerns about the quality of a statistical analysis get in the way of that.

I stole most of this material from Matt Parker, who describes himself as a standup mathematician. (I know!) Anyway, if you’re interested, here’s his take on the issue: