Do you run a bit? If so, chances are you can run 100 metres in 17 seconds. Which puts you in the same class as the Kenyan marathon runner Eliud Kipchoge.

Just one small catch: you have to keep that pace going for 2 hours.

In an earlier post I discussed how Kipchoge had made an attempt at a sub-2-hour marathon in Monza, Italy, but failed. Just. Well, as you probably know, this weekend he successfully repeated the attempt this weekend in Vienna, beating the 2-hour milestone by almost 20 seconds.

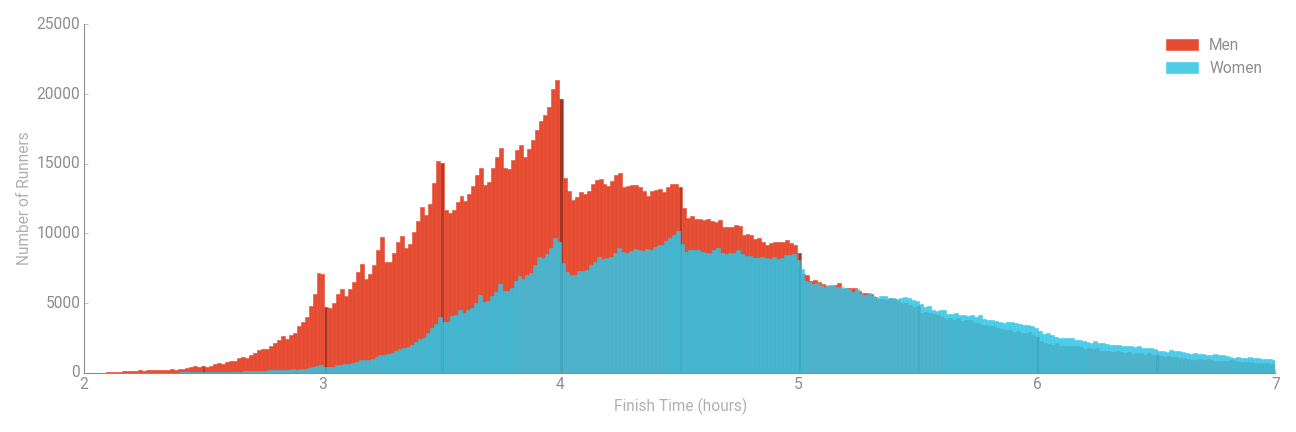

The theme of that earlier post was whether Statistics could be used to predict ultimate performance times: what is the fastest time possible for any human to run 26.2 miles? There must be some limit, but can we use data to predict what it will be? I included this graph in the previous post to make the point:

This graphic is actually unchanged despite Kipchoge’s Vienna run because, as in Italy, the standard IAAF conditions were not met. In particular:

- Kipchoge was supported by a rotating team of 41 pace runners who, as well as setting the pace, formed an effective windshield;

- A pace car equipped with a laser beam was used to point to the ideal running point for Kipchoge on the road.

So, we can’t add Kipchoge’s 1:59:40 to the graphic. But, his race time demonstrates that 2 hours is not a physical barrier, and one might guess that it’s just a matter of time before a 2-hour marathon is achieved under official IAAF conditions. Probably by Kipchoge.

Other things were also designed to maximise Kipchoge’s performance:

- The race circuit was completely flat;

- Kipchoge was wearing specially designed shoes (provided by Nike) that are estimated to improve his running economy by 7-8%.

- His drinks were provided by a support team on bicycles to avoid him having to slow down to collect refreshments.

- The event was sponsored by Ineos, a multibillion dollar chemical company (with a dodgy environmental record.)

Nonetheless: what an astonishing achievement!

Undoubtedly there is a limit to what’s humanly possible for a marathon race time, but records will almost certainly continue to be broken as the limit is approached in smaller and smaller increments. However, as discussed in the original post, Statistics is unlikely to provide accurate answers to what that limit will be. An analysis of the available data in 1980 would most likely have suggested an ultimate limit somewhere above 2 hours. But seeing the more recent data, and knowing what happened at the weekend, it seems likely that this threshold will be eventually broken in an official race sometime.

This is a bit misleading though. What we’ve discussed so far is extrapolating the data in the graph above without taking their context into account. Yet the data do have a context, and this suggests that, above and beyond improvements in training regimes and running equipment, the ultimate limit will be determined by the boundaries of human physiology. And this implies that biological and physical rules will apply. Indeed, research published in 1985 suggested an absolute limit for the marathon of 1:57:58. This research comprised of a statistical analysis, but in combination with models of human consumption of oxygen rates for energy conversion. Who knows if this prediction will stand the test of time or not, but the fact that it is based on an analysis which combines Statistics with the relevant Science suggests that it is more reliable than an extrapolation based solely on abstract numbers.

Footnote 1:

An article in the Observer on Sunday described Kipchoge’s Vienna run in a similar context, discussing the limits that there might be on human sporting achievements. It also listed a number of long-standing sporting records, including Paula Radcliffe’s record women’s marathon time of 2:15:25, which was made in 2003. By Sunday afternoon that record was smashed by a margin of 81 seconds by the Kenyan runner Brigid Kosgei.

Footnote 2:

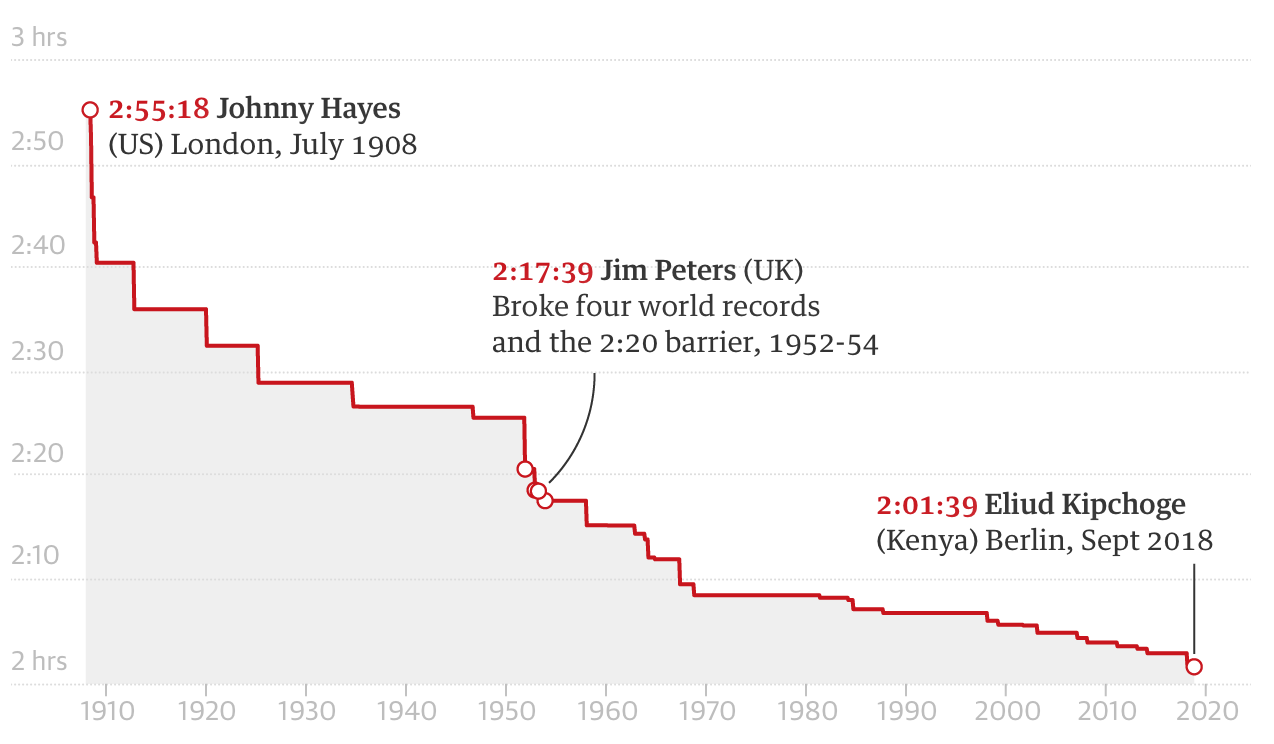

For most people running marathons, the 2-hour threshold is, let’s say, not especially relevant. Some general statistics on marathon performance from a database of more than 3 million runners is available here.

It includes the following histogram of race times, which I found interesting. Actually it’s 2 histograms, one in blue (for women) superimposed on that in red (for men).

Both histograms have unusual shapes which seem to tell us something about marathon runners. Can you explain what?

I’ll update this post with my own thoughts in a week or so.