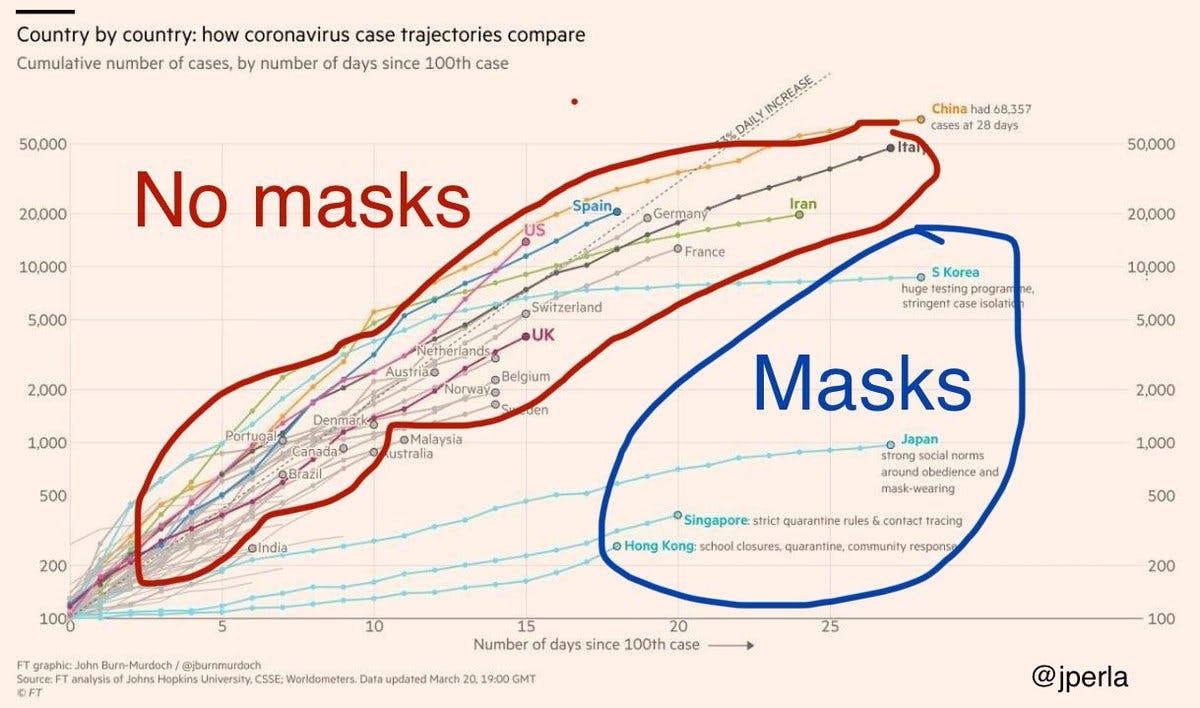

The following graph has been around on social media for a while now:

I’m pretty sure this it was never intended as a serious statistical analysis, but there is, admittedly, a perfect classification in the epidemic trajectory between countries that have and haven’t required the use of face masks for public use. But there are many other factors that may explain the differences – not least geography – and it’s obviously wrong to assume that the wearing of masks is the principal cause.

Still, it’s noticeable that in countries like South Korea, that managed to control the outbreak at an early stage, the use of face masks in public is considered almost mandatory. This point is explicitly made in a Royal Society report written to inform the UK Government’s scientific committee set up to handle the coronavirus epidemic. Their summary reads:

This evidence supports the conclusion that more widespread risk-based face mask adoption can help to control the Covid-19 epidemic by reducing the shedding of droplets into the environment from asymptomatic individuals. This is also consistent with the experiences of countries that have adopted this strategy.

In other words, the scientific evidence points to masks being helpful in reducing the spread of the virus from infected to uninfected individuals. And in addition to the scientific evidence, there is circumstantial evidence that countries that have widely adopted the use of face masks have been successful in containing the spread of the virus.

The report itself is essentially a review of the scientific literature – much of which is very recent – into the effectiveness of wearing face masks as a protection against infection. One of the articles included, published by the British Medical Journal, is especially interesting. It makes these points:

In the face of a pandemic the search for perfect evidence may be the enemy of good policy. As with parachutes for jumping out of aeroplanes, it is time to act without waiting for randomised controlled trial evidence.

That’s to say, in an ideal world, if you want to statistically test the efficacy of something, you would carry out a randomised trial in which you compare results on one group which is given the treatment, and a control group which is not. Essentially the A/B trial approach discussed here. But in the midst of an epidemic – just like jumping from an aeroplane – there’s no time to worry about whether parachutes are effective or not. The parachute almost certainly won’t do you any harm, so you may as well release it.

On this basis they conclude:

-

The precautionary principle states we should sometimes act without definitive evidence, just in case

-

Whether masks will reduce transmission of covid-19 in the general public is contested

-

Even limited protection could prevent some transmission of covid-19 and save lives

-

Because covid-19 is such a serious threat, wearing masks in public should be advised

Other literature covered in the Royal Society report – for example, this article – provides more explicit evidence from statistical studies that the wearing of masks is effective in reducing virus transmission. Again, not in terms of preventing the wearer from becoming infected, but in reducing the risk of the mask-wearer, who may be an asymptomatic carrier of the virus, from passing it on. That’s to say, the evidence points to mask-wearing as having a similar contribution to epidemic control as social distancing: it doesn’t eliminate anyone’s risk of catching the virus, but plays a part in reducing the overall transmission rate, and is therefore an important contributor to disease control.